On July 9, 2024, Virginia Governor Glenn Youngkin issued Executive Order 33, mandating cell phone-free schools to combat the youth mental health crisis. The order cites CDC data showing that, between 2010 and 2021, the rate of suicide has increased 167% since 2010 for girls and 91% since 2010 for boys. Within the same timeframe, boys and girls experienced a spike in depression of 161% and 145%.

These figures are staggering—but banning phones in classrooms is like confiscating lighters while ignoring the wildfire. The real inferno? Social media.

Autumn Kelland, the school-based therapist with the Rockbridge Area Health Center, points out the distinction. “Are we talking about cell phones or social media? Because there’s a difference.” She’s right, cell phones are tools, but social media is a toxin. Platforms like TikTok and Instagram aren’t just apps; they’re slot machines built to hold user attention.

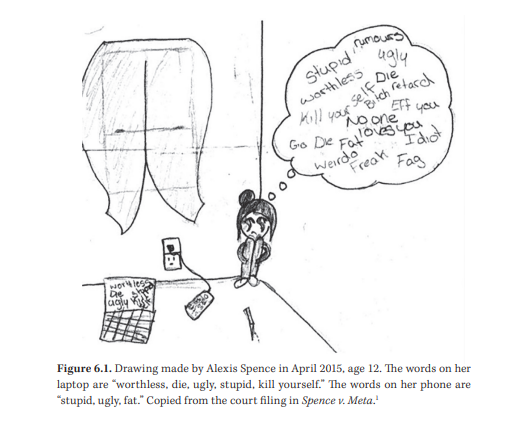

A report by the Wall Street Journal revealed that internal research at Meta showed that Instagram could have adverse effects on the mental health of young users, particularly teen girls, using company reports released by a Meta whistleblower.

With that being said, let’s crunch the numbers. A 2022 Pew Research Center study found that 46% of teens have experienced cyberbullying. Body image issues? Girls aren’t alone. Boys now report unprecedented rates of muscle dysmorphia, with social media use contributing to body dissatisfaction among adolescents.

Even further still, a 2024 study by the Center for Countering Digital Hate found that teens on TikTok encounter harmful content within minutes. “For our study, CFDH researchers set up new accounts in the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia at the minimum age TikTok allows, 13 years old. These accounts paused briefly on videos about body image and mental health, and liked them. What we found was deeply disturbing. Within 2.6 minutes, TikTok recommended suicide content. Within 8 minutes, TikTok served content related to eating disorders. Every 39 seconds, TikTok recommended videos about body image and mental health to teens.”

And it’s incredible that people still wonder why we’re all so self conscious about the way we look and present ourselves, when the evidence is contained right within their phones.

The damage isn’t limited to a single person’s mental health. The influence of social media on mass shooters is, unfortunately in this day and age, a concern for everybody. Recent incidents show that the perpetrators typically engage with radical extremist groups on social media, consequently amplifying their violent tendencies.

The Colorado Information Analysis Center published data relating to shooters and their social media tendencies. A few quotes from the report:

“The 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary School shooter posted frequently on internet forums and had Tumblr blogs named after school shooters, which he deleted a month before the shooting.”

“Less than 6 months before 17 people were fatally shot at a high school in Parkland, Florida, for example, the shooter posted a comment to a YouTube video that read, “Im [sic] going to be a professional school shooter.” The shooter also proudly proclaimed he would become “the next school shooter,” in cell phone videos he made of himself just before the attack.”

Moreover, other reports suggest that the pervasive nature of social media can act as a catalyst to violence among youth; many mass shooters showed trends of socializing with online extremist groups and being victims of, or engaging in, cyberbullying. Social media served to escalate conflicts that might have otherwise remained contained. So who’s to blame? The gun manufacturers, or the Silicon Valley multibillion dollar tech corporations who put the idea in their heads?

If corporations wanted to stop kids from accessing it, they could, but money talks louder than increasing suicide rates, mass shootings, and an overall increase in other related mental health issues. Skeptics are already whining about “overreach.” Tell that to parents burying children who spiraled after relentless cyberbullying. Tell that to schools scrambling to counsel elementary-level students exposed to graphic violence online. And let’s be honest: teens survived without Snapchat in 2005. They can survive without it in 2025.

Other countries like Australia and France aren’t waiting for Silicon Valley to grow a conscience. Australia’s proposed ban on social media for children under 16 and France’s restrictions for users under 15 signal a global shift in awareness. Critics argue age verification on such a massive scale is impossible, but they’re already being proven wrong. Companies like Yoti, which uses AI for facial age estimation, have proven that age verification without identification is possible.

The phone ban is a start, but it’s toothless without tackling social media’s stranglehold. “Students are adapting,” Kelland said, noting halls buzzing with social chatter post-ban.

But chatter won’t fix algorithmic harm. Utah and Arkansas have already passed laws requiring parental consent for minors’ social media accounts, and an American Psychological Association advisory urges developers to take action to curb harmful platform designs. These suggestions aren’t based on the foundations of radical politics—it’s purely survival.

Bottom line: Phones in backpacks won’t stop a 13, or even a 17-year-old from doom scrolling TikTok at 2 in the morning. It won’t delete the hate comments infesting their posts. Social media is global. The damage doesn’t stop at the school door. Until we treat it like the public health emergency that it is with real, enforceable legal action; we’re just slapping band-aids on bullet wounds.