Procrastination Provides Purpose

May 26, 2017

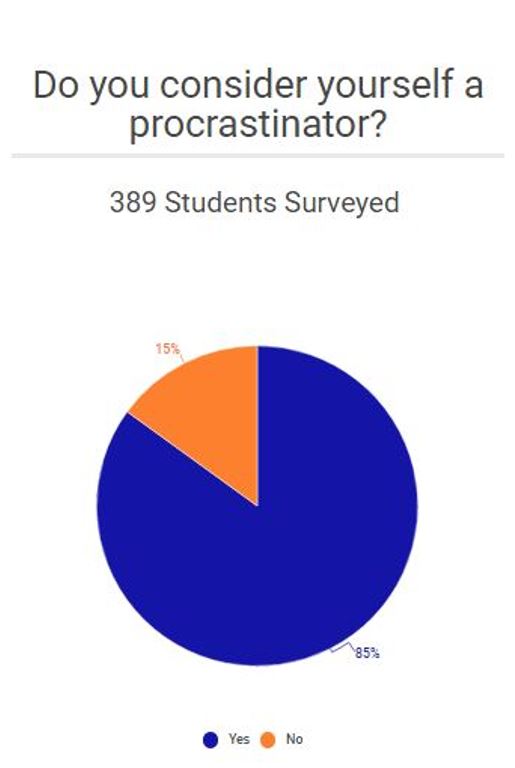

Sometimes the urge to avoid an unavoidable task, such as homework or chores, is too strong to ignore. Regardless of the fact that it will have to be done eventually, you just keep pushing it further and further ahead until it needs to be done. While some people may procrastinate more than others, it affects just about everyone. Procrastination is clearly more than just a refusal to manage time wisely. Despite the stigma that procrastination is equivalent to laziness, my experiences suggest otherwise: that procrastination is a legitimate struggle.

One thing that all procrastinators dread is a long-term assignment. The ideal workload for a long-term assignment is spread out evenly. Work intensity might gradually increase as the deadline nears, but the work is done in a steady stream.

Procrastinators always want to work this way. We plan to manage our time like this, and most procrastinators get very close to starting the assignment, but we never do until it is too late. Our brains seem to be physically unable to begin working efficiently. Why?

I think that this is because procrastinators think differently than non-procrastinators It seems to me that procrastination feeds voraciously off of individuals with two characteristics: the tendency to enjoy temporary rewards and the tendency to work well under pressure.

For example, say an assignment is due in a month, and a student is faced with a large amount of free time. Most students would be able to recognize that this is a good time to get work done, but few actually would work. The sense of urgency is just not there. Since the deadline is so far away, the urgency of the situation is minimal. Even though the students know they should be helping their “future selves” out, there are more fun things to do at the moment.

This is the first characteristic of procrastination. Procrastinators pursue small, often meaningless, temporary rewards (by doing fun things such as surfing the internet or playing a game) rather than long-term, meaningful rewards (by getting a head start on the big paper).

Some people may have this first characteristic but are not chronic procrastinators. That is because they are lacking the second characteristic of procrastination: working well while under stress. Maybe a student is tempted to pursue a temporary reward of slacking off, but knows that doing so would make them unable to do their best work in the future.

For a procrastinator, the threat of an imminent deadline is the exact energy boost needed for completion, and there is no better motivator than complete and utter panic. When a masterful procrastinator is threatened by a dire consequence, he is prompted to do his work quickly, effectively, and, in general, quite well.

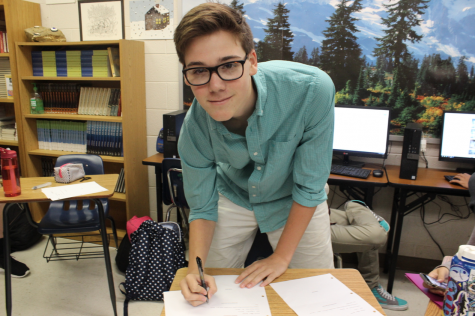

Take it from sophomore Rachel Maxwell, a self-proclaimed procrastination aficionado. Maxwell, and many others like her, understand that they have a problem and would like to do something about it. Her relationship with procrastination has been going strong for a long time, and she’s become familiar with the tips and tricks of the trade.

“ Once you start working on the assignment that you’ve put off, really focus in on it,” said Maxwell. “Put away all the electronics, get out all your stuff, and just crank it out for two hours.”

The clinical definition of procrastination portrays the habit as a bad thing, and I will not argue with that. Procrastination is, in many ways, a debilitating condition, but with enough practice, one can master the art. After years of shameful, yet successful, all-nighters, procrastination becomes routine. The sacrifice that procrastinators make is an exchange: several weeks of blissful ignorance for one or two days of blood, sweat, and tears. Some people scoff at this lifestyle, while others thrive in it.